WASHINGTON, D.C. – Earlier this week, United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) issued a new federal order requiring all dairy cattle to be tested for bovine influenza A, also called H5N1, (also known as highly pathogenic avian influenza in poultry and birds) before being moved across state lines. It also requires tracing the previous movements of dairy cows from infected herds. Dairy cows testing positive will be quarantined for 30 days and then retested.

Laboratories and state veterinarians will also be required to report any positive virus findings in livestock to USDA. Testing and mandatory reporting will be enforced beginning Monday, April 29.

That was followed by the announcement on Thursday that an estimated fifth of the U.S. milk supply contains fragments of the virus. The Biden administration and dairy industry are racing to convince the public not to worry about the spread of the disease among the nation’s dairy cattle or the safety of the nation’s milk supply.

USDA first announced finding a strain of the bird flu in dairy cattle in Kansas and Texas on March 25. Since then, the virus has been found in dairy cows in eight states, including South Dakota.

Other states that instituted strict guidelines to restrict dairy cattle imports from those states with H5N1 cases following the USDA announcement in March, have remained virus free for the most part. States with restrictions include Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Delaware, Florida, Hawaii, Nebraska, Idaho, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Utah, and West Virginia.

In dairy cows sickened by H5N1, milk production drops sharply, and the milk becomes viscous and yellowish. “We’ve never seen something like this before,” said Dr. Keith Poulsen, director of the Wisconsin Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory. The virus runs its course in a matter of days with full recovery, according to officials.

Virus Outbreak Threatens U.S. Dairy Industry 〉

Virus Outbreak Threatens U.S. Dairy Industry 〉

There is some reassuring news: At a recent meeting, scientists from USDA said the virus is not presenting like a respiratory illness in cattle – meaning the animals don’t appear to be shedding large amounts of virus from their nose or mouths.

Instead, federal health officials investigating the outbreak suspect some form of “mechanical transmission” is responsible for spreading the virus within the herd. This may be happening during the process of milking the cows, a theory supported by the fact that high concentrations of virus are being found in the milk.

Federal officials and industry executives maintain the discovery of inactive fragments of the virus strain, known as H5N1, in milk sold to consumers is not, in and of itself, worrisome — rather, it’s evidence that the pasteurization process is working to neutralize the virus. But given that bird flu has never before spread to dairy cattle, public health officials warn there are still many unknowns. And they and some farmers and lawmakers are now urging the government to rapidly expand its testing and research — and to make that data available ASAP.

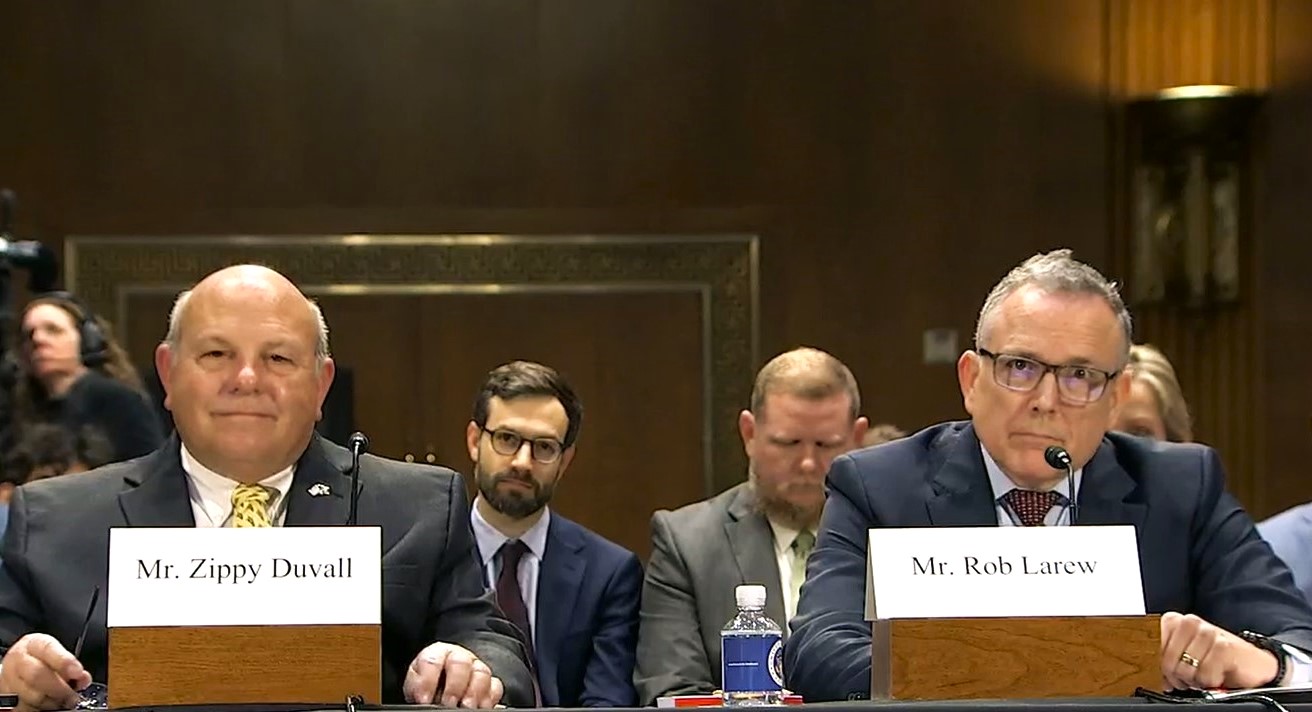

In an April 24 letter to Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack, Sen. Tammy Baldwin (D-Wisc.) urged the USDA to “quickly deploy additional resources in states that have the opportunity to prevent the disease from entering herds within their borders by working directly with farmers on improving their biosecurity options.”

Several farms in Minnesota — not one of the eight states with known cases — are sending samples of cow blood to private labs to test for antibodies to the virus, which would indicate a current or past infection, said Dr. Joe Armstrong, a veterinarian at the University of Minnesota Extension. Other dairy farmers are reluctant to test, worried that fears about bird flu could hurt their business, said Dr. Amy Swinford, director of the Texas A&M Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory.

The World Health Organization has noted that while the risk from H5N1 to the general public is “low,“ there is a “low-to-moderate” risk of infection for farmworkers and others regularly exposed to dairy cows. The one case in which a human has been infected by this latest outbreak of the virus was a dairy worker in Texas. That case, that presented as conjunctivitis, resolved itself with treatment.

HHS for Preparedness and Response Assistant Secretary Dawn O’Connell told reporters on Tuesday that if needed, hundreds of thousands of doses of vaccines that target the H5N1 avian flu virus in humans could be deployed within weeks, pending Federal Food & Drug Administration action. Over 100 million doses could then be deployed within months. States can also request personal protective equipment from the national stockpile to help protect farmworkers and others in close contact with infected animals, officials said.

So far, H5N1 in dairy cattle seems to affect only lactating dairy cows, and only temporarily. There have been no diagnoses in calves, pregnant heifers or beef cows.

“This is a big story for the dairy industry, and for the cattle markets,” Arlan Suderman, chief commodities economist at StoneX Group, told MarketWatch recently.

USDA is exploring vaccines to protect cattle from H5N1, but it is unclear how long it might take to develop them. Dr. Armstrong, of the University of Minnesota Extension, said many dairy farmers and veterinarians hope the virus will “burn itself out.”

But if it were to become a long-term problem, “The goal is to prepare for that,” he said. “Not for this wishful thinking of, ‘It’ll just go away.’”